A ship is fundamentally a machine—an instrument of marine transportation, ocean commerce, and naval warfare.

But to those who create it, to those who sail or encounter it, and indeed to those who study the records of one long past, a ship is a great deal more. It is a highly sophisticated artifact of human ingenuity. It takes on vibrant life and distinct personality. It engages the passions.

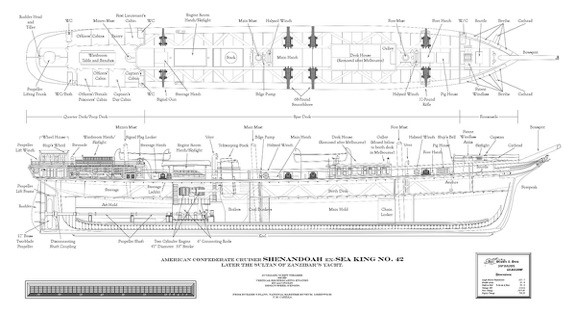

The CSS Shenandoah was a magnificent vessel, a reflection of a rich maritime heritage. The square-rigged sailing ship is among the oldest and the most complex creations of the human race, evolving slowly over millennia from fundamental concepts.

For five centuries these vehicles dominated the oceans and enabled global civilization. Probably no other single technology had such far reaching impact over so immense a span of time. They reached their most effective as well as their most aesthetically pleasing expression in the clippers.

But in a few decades, natural elements of wood, hemp, and canvas would give way to forged and manufactured materials of iron and steel. The siren call of wind in the rigging was silenced by the thump of the engines and the roar of mechanical blowers; the fragrance of the sea was tainted by coal smoke.

Shenandoah was a paradigm of dramatic transitions in the midst of the industrial revolution, and she presented stark contradictions: a valiant warship to Southerners, a hated pirate to Northerners. She was a swift and graceful tea clipper and a state-of-the-art steamer, an amalgam of wooden hull and iron frames, the epitome of the ancient art of tall ship construction and a prime example of the new technology of the machine age.

Shenandoah represented the quintessence of commercial sail while serving as one of history’s most effective commerce destroyers. Nearly perfect for her mission, she was a new kind of warship, a prototype of cruisers to follow and an example for raiders stalking the oceans through the world wars.